Early Days at the Movies

Fanzine

Real Women in

the Movies

Just Kidding

The Seventh Art's Seventh Heaven

So What Happened

Next?

POETRY AND PROSE

Aperçus

Répérés

Choses Vues

Zastrugis

CHOSES

VUES

A

Short for the Long Fellow

IM

John Heath-Stubbs (1918-2006)

Less a

The

slapstick of poetry

was yours. But the laugh was not a line. When the leaves fell you stood

out,

looking as though struck by lightning. Your eyes were yokes.

Those who

sat at your

feet were playfully kick-started into a world where to know where you

stood was

to become your own statue. So leglessness was a solution. I see you

reflecting

in tranquility on a cloud, gently mocking Wordsworth.

‘Shelley is another

matter’, you said. That was final. I thought you were Walter

Savage Landor

crossed with Coventry Kersey Patmore with a touch of Peacock. You had

more

staying power than George Barker because you knew how to move on.

I’d

be happy to grant

the Queen of England a pardon if she made you the Poet Laureate

posthumously.

Or at least Poetry’s Head Gardener. Your topiary could rise

to any occasion.

This would mean weeding out Andrew Motion, and uprooting the common

ground to

plant proud oaks. ‘The present is beyond redemption. So much

has been allowed

to go to seed since classical times. It’s time to civilise

the past.’ The watch

you consulted was stopped.

You walked

in Hampton

Court, amongst the labyrinth of box trees, and ever-so-scarcely noticed

the

people laughing as you emblazoned roses on bowers. What a sensible

commotion

you created around you. But the mind has its own order, and your poems

found

their place. Stubbs in the Heath. ‘Where are my

cigarettes?’

Home

‘How angry the

Nid

de poule is

the French for potholes. We have been rerouted off the motorway because

of the

storm. I’m driving on eggshells. Suspension, suspense.

Don’t get worked up

you’re working me up. ‘A

temps-pest could translate nuisance weather’, I say.

The

storm

disappears back into the mountains, flashing sheets of light. Static

lingers in

the air. The air terminal is suddenly there. ‘Not this desk,

but the one over

there’, says check-in, ‘and then come

back.’ Real money is refused though the

computer won’t register my plastic.

Don’t get worked up

you’re working me up.

‘Won’t you even take a bribe?’ I say,

fingering my wad. An officious woman does

not smile. I see the last of you, boarding. People before walking on

air always

look lost. But you know where you’re going, destination

announced. The steps

are being wheeled away.

Returning,

I

could be taking off on wings of spray as I plough through the flooding.

The

drain before our door is clogged with leaves. In this downpour I might

as well

swim in the sea. I find a cave for my clothes and jump in. The shock of

the

cold. The sun has not shone for three days. Floating, I think I see

your plane

pass overhead.

I

take to my

bed, and dream of a simpler time. Waiting together in a small airport

in the

middle of nowhere. You are reading, and I am pacing around. We are

going to the

centre of the world where nobody has a shadow.

I

wake up and I

hear myself saying, I’ve shared most of my life with you and

I don’t know who

you are. I am talking to myself. It’s after midnight. You

will have landed by

now. I can’t wait for you to boomerang back.

The Mystical

Tapestry

Paul Valéry, examining figures

embroidered in silk

by an unknown medieval artist, attributed to the tapestry a mystical

dimension.

Held up to the light, the figures disappear in the hunting scene,

transforming

the tapestry to its essence, the artist’s chase to hunt down

with his hand and

eye the soul of his craft and make it his own. The threads drawn to

entwine

that coming together could be unravelled from his life, and the

peasants around

him who cultivated silk worms and harvested them, the makers of the

mysterious

dyes, the nobleman who ordered up a scene from his life to be captured

in silk.

Valéry concluded that if you only see a hunt you see

nothing, nothing you have

not seen before.

Bouleverser

IM M. Guittet Endymion

(1965-2006)

The thin man is beautiful when he plays

boules. The

run up is as smooth as that of a slow medium paced cricket bowler, only

the

delivery is underarm. The whip of his action is almost invisible. The

ball

flights and curls in the air.

Thin

is an

exaggeration. He scarcely exists beyond the one-dimensional until the

wisp of

his body elongates in full flow. Close cropped head round as the ball,

white

drainpipes, tight vest, springy trainers soled with a doorstep of crepe.

He

plays

Lyonnaise boules, a game for warriors which is disappearing into a

postprandial

pastime to work off the wine. Common boules, with its stand-start and

egg and

spoon follow through, is the French equivalent to a constitutional.

Nevertheless

it

has a national federation with ambitions for boules as an Olympic

sport. Though

it’s only a few steps above watching television. The name has

been changed to

pétanque and competitions regularised. But the image of

tipsy types with butts

stuck to the lip with nothing better to do dies hard. Wherever there is

bare

ground in

The

thin man

lives across the landing with a round-faced woman of a certain age

whose eyes

go rheumy when she smiles. He is the houseboy, I think. She never goes

out.

Glimpses of their apartment intimate genteel disorder. Sometimes he

brings her

flowers.

In

the small

hours the thin man practises in the square by the light of the moon. He

throws

a wooden ball studded with nails rather than the common steel one. I

don’t

understand the game any more than ballet. So I don’t know how

good he is. But I

recognise a Nureyev when I see one.

When

I meet him

at Chez Martial, the baker, he is as formal as a famous sportsman. The

hand is

firmly pressed with the ‘Comment allez-vous?’

I ask him, ‘How goes the

boules?’, and he answers, ‘I haven’t got

it right yet’. His morning breath

smells of wine. Welsh tells me it’s his medical preparation.

He paces himself

through the day with libations which give him confidence and a steady

hand.

White wine is his beta-blocker.

The

federation

has banned smoking and drinking in competitions, and made uniforms

compulsory.

Clubs are applying the rules draconically. The thin man has been

dropped from

the local team. He refused to wear the standard issue gear and

sometimes lapsed

into Lyonnaise in the middle of a match.

The

nocturnal

practising continues. The thin man performs to the moon, sharp now as a

blade

of grass. As dawn comes up he goes home. Often he is locked out. I hear

him

banging on the door. Sometimes he sleeps on the stairs.

The

other night

he did not return. Nobody knows where he is. Some say he tried to

embrace the

moon over the yellow river. I know better. The moon descended on the

thin man

and kissed him, and he fell into an everlasting game of boules for her

to watch

forever without disturbance. The wooden ball studded with star shards

donkey-drops

on the red marble, and ricochets off the yellow one.

Eyes

IM Claude Jade (1948-2006)

You had the second best eyes in French

film. I see

them regard J-P Leaud with amused pity in Truffaut’s Stolen

Kisses.

Arletty’s as Garance in The Children of Paradise visited

J-L Barrault’s

with pitiless love. Hers were golden-blue, yours blue-grey with a

silver

lining. But they came from the same sky.

Eyes

that say

everything are not good. When least expected they turn on themselves.

Arletty

lost hers to a Luftwafte pilot and, after the war, not being able to

look

people in the eye, they went blind from desuetude. Yours saw the

sadness of

things as they are and disappeared into cancer.

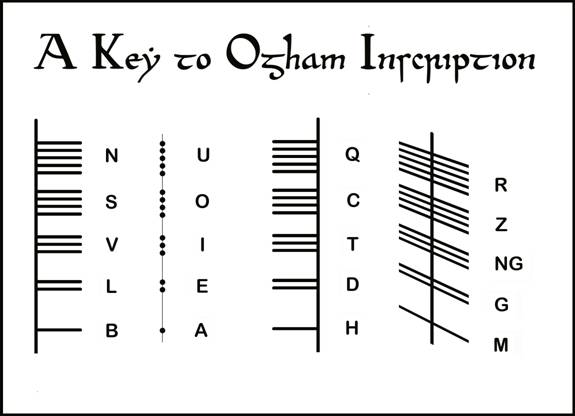

Ogham:

A Conceptual Poem

My original intention was to write a poem

in Ogham.

The Stone Age language of the Celts never had a literature. Its twenty

letters

were cut in diagonal dashes with orb relief, not unlike a game of

noughts and

crosses. They were mainly used to mark property boundaries, warning

notices in

fields.

Beware

of the

Bull of Coolin.

Trespassers

Will Be Prosecuted.

Dropped Out for

Lunch Back in Five Centuries.

Pas de Pub.

Prolonged

That

sort of

thing. Ogham represents the only written evidence in early Irish law.

The poets

perpetuated the statutes orally, not unlike the British Constitution

and the

Law Lords. I dropped the idea of an Ogham poem.

But

for those

who wish to rise to the challenge here is the Ogham alphabet (artwork

by Marita

Llinares):